- HOME

- category

- Life & Politics

- category

- Literature & Art

- category

- Looks

- İzmir’s women fight against violence through art and law

İZMIR’S WOMEN FIGHT AGAINST VIOLENCE THROUGH ART AND LAW

As expected from a city founded by Amazons, the women of İzmir are fighting violence against women through art, theater and a strong determination to take offenders to court.

The tradition of talismanic shirts – known as the Ottoman magic shirts- dates from Turkey’s shamanist past. Back then, the shirts, engraved with geographical designs, were believed to protect the person who wore them against diseases and enemies.

With Islam, the geographical designs became verses from Quran and the “talismanic shirts” entered the Ottoman Palace, to be mostly worn by crown princes, to protect them from the wrath of their brothers and contenders to the throne or to assure they had plenty of offspring to ensure their line of blood continued.

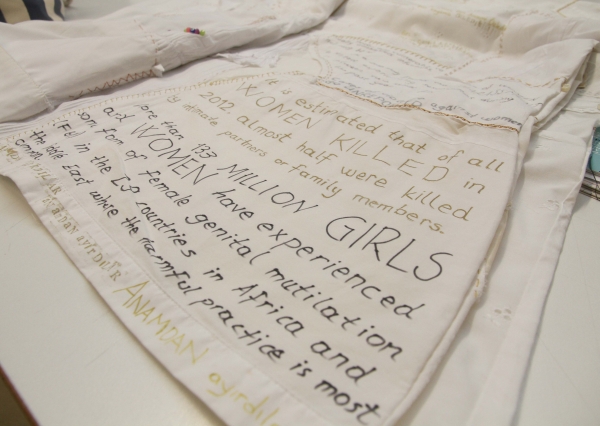

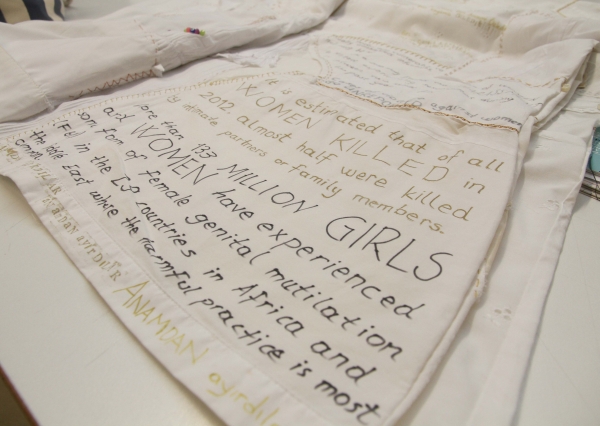

Elvan Özkavruk Adanır and Jovita Sakalauskaite Kurnaz, both artists and academics at İzmir Economy University, have decided to “feminize” this masculine tradition to raise awareness about violence against women in their project “Denial of Fear and Despair: Talismanic Shirts.”

Their friends joined the project happily when Adanır and Kurnaz asked them to donate white shirts to show their support for women who face physical and/or sexual violence or abuse.

“We thought that getting women from different cities to contribute their shirts would also help create awareness,” said Adanır. “Sixty-five women living in İzmir, İstanbul, Antalya, Hatay, Essen, Klaipeda, Kaunas and Vilnius supported the project by donating their shirts. [From these] 21 shirts were created by cutting and joining different pieces together. The largest one contains the names of the women who contributed.”

Unlike the original talismanic shirts that carry prayers, verses from Quran and religious symbols, these shirts carry cries and hopes of child brides, young girls and women. Statistics about violence against women in Turkey, Lithuania and the world are printed on the shirts. Some of them carry songs talking of the longings of women, heart-breaking phrases such as “save me from this hell” from a rape-victim and pictures of women whose mouths are closed.

Domestic violence against women has been reflected in theater as well. The Han Theater, one of the young, private theaters of the city, ran a play called “No Food in the House, So We’ll Be Beaten Again” for two seasons. The tragic-comic one-act play is about two women shut away by their husbands in a slum, who decide to have a day of folly before they commit suicide: they’ll eat a pizza and get their first – and last– orgasms with the help of a delivery boy.

Who’s the top?

A year ago, the Health Ministry released a “violence map of Turkey,” showing İzmir as the city with the highest case of violence against women. In August 2014, Health Minister Mehmet Müezzinoğlu announced that out of 12,946 cases of violence against women, 1,213 were from İzmir, the highest number in Turkey. However, according to the same map, there were 52 cases of violence against women from Diyarbakır and 45 from Konya.

İzmir’s women (and men) reacted to the headlines and numbers with skepticism. İzmir Bar Association’s Ayşegül Altınbaş accused the minister of being biased and trying to defame a city that has traditionally stood against the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government. “Has there been a feminist revolution in [the conservative cities like] Muş, Ağrı and Bitlis that we have not been aware of?” she asked, claiming that the figures were based on cases reported to the police and ignored those who went to the civil society or simply kept silent. According to the local jurists and columnists, the map only shows that women of İzmir find it easier to report the violence against them than their counterparts in Konya.

The İzmir Bar Association has a special branch to help victims of domestic violence as well as a helpline. They also keep a sharp eye on those who encourage violence against women. For example, when the chairman of İzmir-based Divorced and Victimized Fathers’ Association was quoted in an interview that he “congratulated heroic fathers who killed their wives,” İzmir Bar’s Women Rights and Legal Research Center Chair Kadın Nuriye Kadan evoked a case against him.

Muhammet Özen, both chairman and a teacher, allegedly said that laws and state policies victimized divorced fathers by letting women have everything in the divorce: “The state gives men two options: either to pay alimony all his life or kill his wife,” he was quoted as saying. His efforts to duck court, where he is charged with five to ten years for encouraging crime, did not pay. He was taken under custody a week ago.

“When we started work on the talisman shirts and violence, we did not fully realize the extent of the violence,” said Adanır. “That is why we ended up with naming the project ‘Denial and Despair’ – very few of us know the true extend of violence against women. What will protect them in the 21st century?”

Perhaps the reply lies in a strong civil society, strong laws and a determination to enact them. But art will certainly help.